Skins Gambling Com

Virtual goods purchased with microtransactions and then used to gamble or bet.

Good CSGO Gambling Sites have nice and fair gamemodes like Roulette, Crash, Betting, Case Opening and Jackpot. They have low fees, many withdraw options and do real CSGO skin giveaways. A good site should be in english and offer CSGO skins.

What are skins?

A skin changes the look of an item in a video game. For example: the same gun in a game can have different ‘skins’. The skins make the gun look differently.

Skins are either earned within a video game or they can be purchased in the game’s store.

Skins are purely cosmetic so they don’t change the gameplay or they don’t make you a better player.

Some skins are rarer than others. So players with a rarer skin gets a certain recognition. Quite similar to branding on clothes.

Skin betting is when skins are used to bet or for gambling. These skins become the tokens you can gamble with.

Your child plays a game and purchases or wins some skins.

The player takes their wallet to a different website.

The player bets/gambles using skins as their tokens.

The skins won can be traded for real money in some games.

Gamers spent an equivalent of over $5 billion on Counter-Strike: Global Offensive skin gambling during 2016.

Eilers & Krejcik Gaming and Narus Advisors

Help for parents

Where did skins come from?

We would like to show you a description here but the site won’t allow us. CSGOMeister.com is a guide and comparison website focusing on skin gambling and esports betting. Our team consists of 4 experts with different backgrounds, interests and gaming experiences. Our vision is to help all players choose the best available gaming site for their needs. We also want to make the skin gambling.

It started around 2012 when Valve introduced skins in Team Fortress 2 and CS:GO. They were added to create more excitement and player engagement. Skins were seen as a reward, an enticement to play their game.

Valve also created a marketplace for skins. Players could trade skins with each other and collect skins.

Turned out that the colourful skins were most popular and people wanted them because of their trophy value. It showed up the player’s skill.

By making some skins rarer than others, Valve engineered a value for these skins. Rarest skins were highly sought after and consequently attracted a higher price. Some skins are worth over $3,000.

Skin trading became really popular and a lot of trading was done on Valve’s marketplace. Skins became a virtual currency.

For every trade made on Valve’s marketplace Valve takes a 15% transaction fee.

Around 2015, as popularity increased, other websites popped up using Steam’s API. This means players could trade with their skins on websites completely outside of the game. These websites also allowed players to deposit and withdraw real money which was converted into skins.

These websites quickly added gambling features and offered games like roulette, coinflip and other traditional gambling games.

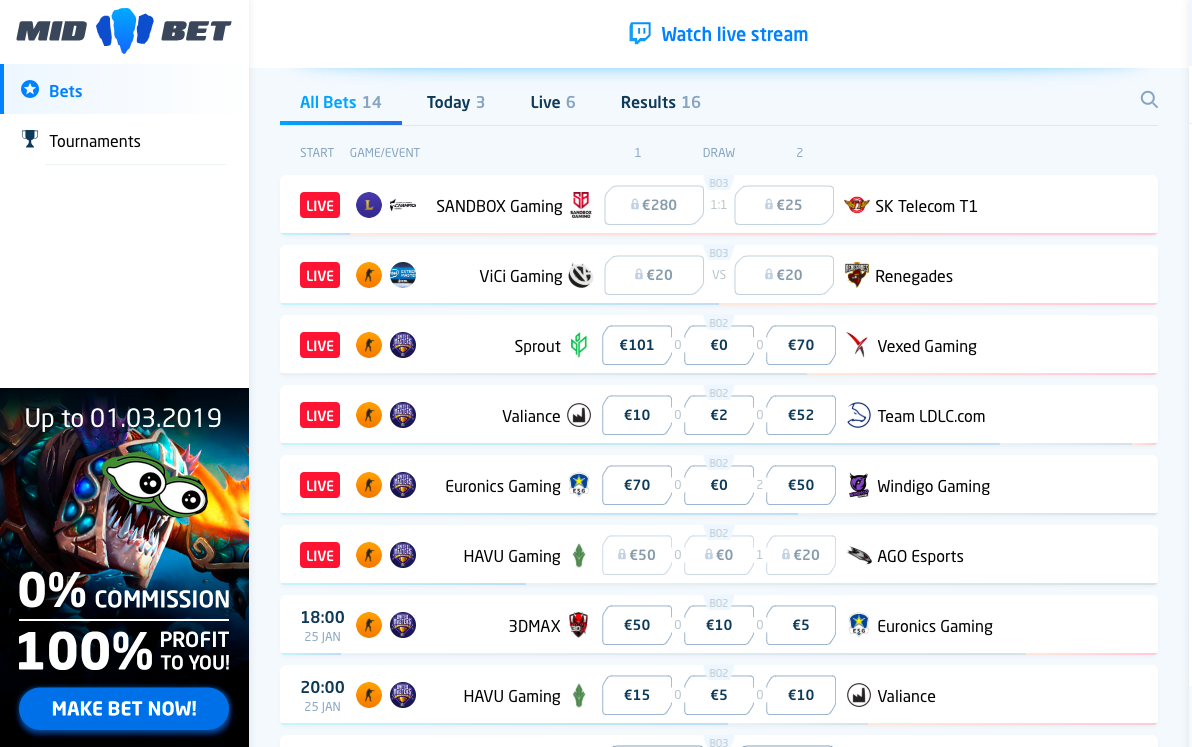

With the rise of E-sports (competitive gaming) these websites offered the opportunity to players to bet with skins on their favourite e-sports teams.

Skin betting is not governed by gambling law because skins are not considered to be ‘real money’

Skin betting websites

Skin betting does not usually occur within the actual video game. It happens on separate websites.

Players can take their wallet with their skins to one of these websites to bet or gamble with their skins. This website offers a range of gambling games players can engage with.

Roulette

In roulette the object is to pick the correct color (red, black or green) where the spinning ball will land on the wheel. On some gambling sites you can also bet on numbers and custom colors which can pay up to 50 times your bet. Compared to normal casino roulette, skin gambling roulette usually have a different layout, but the principle is the same.

Coinflip

A simple game where players play 1 versus 1 with a 50% chance of winning. If you win you double up on your bet.

Jackpot

In Jackpot players put their skins into the pot, where one person will win the whole pot. The higher skin value that a player adds to the pot, the higher chance the player has to win.

Case Opening

Case Opening sites offer the same experience as the case openings in the game, but at a reduced cost and with a better chances of winning.

WHAT CAN PARENTS DO?

- Discuss the risks of gaming with your child and encourage your child to reach out for help when needed.

- Don’t give your children access to your passwords. Know which games are downloaded and played.

- Have a play of the game yourself. You’ll quickly work out if the game is appropriate or not.

- Monitor your credit cards and look for unaccounted expenses

- Ask your child how they can best balance screen-time and real life activities. It empowers them to do the right thing.

- Let game developers and government know that you expect games to be designed safely.

WHAT CAN THE GOVERNMENT DO?

- Introduce regulation that ensures that minors are not engaging in predatory lootbox mechanics.

- Fund Education Campaigns so children are aware of the risks of gambling and how they can infiltrate video games.

- Run an awareness campaign about how gambling is found in video games.

- Introduce clear consumer protection guidelines so children do not run the risk of normalising gambling.

- Provide ethical frameworks to the video game industry and engage them into long-term, supportive and collaborative conversations about safety online.

RESEARCH AND EVIDENCE

Abarbanel, B., Gainsbury, S. M., King, D., Hing, N. & Delfabbro, P. H. (2016). Gambling Games on Social Platforms: How Do Advertisements for Social Casino Games Target Young Adults? Policy Studies Organization. Policy and Internet.

Albarrán Torres, C., & Goggin, G. (2014). Mobile social gambling: Poker’s next frontier. Mobile Media & Communication, 2(1), 94–109. doi:10.1177/2050157913506423

Alham, K., Koskinen, E., Paavilainen, J., Hamari, J., & Kinnunen, J. (2014). Free-to-play games: Professionals’ perspectives. In Proceedings of Nordic DiGRA 2014. Retrieved from http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/nordicdigra2014_submission_8.pdf

Bednarz, J., Delfabbro, P., & King, D. (2013). Practice makes poorer: Practice gambling modes and their effects on real-play in simulated roulette. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 11(3), 381–395. doi:10.1007/s11469-012-9422-1

Binde, P. (2014). Gambling advertising: A critical research review. London: The Responsible Gambling Trust.

Blaszczynski,A., Ladouceur, R.,&Shaffer, H. J. (2004).A science-based framework for responsible gambling: The Reno model. Journal of Gambling Studies, 20, 301–317.

Calvin Ayre (2017). Legality of CS GO skin gambling. Available from: https://calvinayre.com/2017/02/23/business/legality-of-csgo-skin-gambling/

Campbell, C., Derevensky, J., Meerkamper, E., & Cutajar, J. (2011). Parents' perceptions of adolescent gambling: A Canadian national study. Journal of Gambling Issues, 25, 36–53.

Castronova, E. (2005). Synthetic worlds: The business and culture of online games. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Casual Games Association. (2012). Social network games 2012: Casual games sector report. Smithfield, UT: Casual Games Association.

Carran, M., & Griffiths, M. (2015). Gambling and social gambling: An exploratory study of young people’s perceptions and behaviour. Aloma, 33(1), 101–113.

Clarke, D. (2008). Older adults’ gambling motivation and problem gambling: A comparative study. Journal of Gambling Studies, 24(2), 175–192.

Derevensky, J.L., & Gainsbury, S.M. (2015). Social casino gaming and adolescents: Should we be concerned and is regulation in sight? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry.

Derevensky, J. L., Gainsbury, S. M., Gupta, R., & Ellery, M. (2013). Play-for-fun/social-casino gambling: An examination of our current knowledge. Winnipeg, MB: Manitoba Gambling Research Program.

Derevensky, J., Sklar, A., Gupta, R., & Messerlian, C. (2010). An empirical study examining the impact of gambling advertisements on adolescent gambling attitudes and behaviors. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8(1), 21–34.

Derevensky, J. L., Gupta, R., Messerlian, C., & Gillespie, M. (2005). Youth Gambling Problems. In Gambling Problems in Youth (pp. 231-252). Springer US.

Dickins, M. & Thomas, A. (2016). Is it gambling or a game? Simulated gambling games: Their use and regulation. Australian Gambling Research Centre.

Eilers & Krejcik Gaming. (2016). Social casino tracker—4Q & 2015. Santa Ana, CA: Author.

Floros, G., Siomos, K., Fisoun, V., & Geroukalis, D. (2013). Adolescent online gambling: The impact of parental practices and correlates with online activities. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29(1), 131–150. doi:10.1007/s10899-011-9291-8

Fong, T. W. (2005). The biopsychosocial consequences of pathological gambling. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 2, 22–30.

Frahm, T., Delfabbro, P. H. & King, D. L. (2014). Exposure to free-play modes in simulated online gaming increases risk-taking in monetary gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies. DOI 0.1007/s10899-014-9479-9.

Friend, K. B. & Ladd, G. T. (2009). Youth gambling advertising: A review of the lessons learned from tobacco control. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy, 16(4), 283–297.

Gainsbury, S., Abarbanel, B., & Blaszczynski, A. (2017). Game on: Comparison of demographic profiles, consumption behaviours, and gambling site selection criteria of esports and sports bettors. Gaming Law Review, 21(8), 575-587. https://doi.org/10.1089/glr2.2017.21812

Gainsbury, S., Abarbanel, B., & Blaszczynski, A. (2017). Intensity and gambling harms: Exploring breadth of gambling involvement among esports bettors. Gaming Law Review, 21(8), 610-615. https://doi.org/10.1089/glr2.2017.21813

Gainsbury, S. M., Hing, N., Delfabbro, P., Dewar, G., & King, D. (2015). An exploratory study of interrelationships between social casino gaming, gambling, and problem gambling. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13(1), 136–153. doi:10.1007/s11469-014-9526-x

Gainsbury, S. M., Hing, N., Delfabbro, P. H., & King, D. L. (2014). A taxonomy of gambling and casino games via social media and online technologies. International Gambling Studies, 14(2), 196–213. doi:10.1080/14459795.2014.890634

Gainsbury, S. M., King, D. L., Delfabbro, P., Hing, N. Russell, A. M., Blaszczynski, A., & Derevensky, J. (2015). The use of social media in gambling. Gambling Research Australia, Department of Justice, State of Victoria

Gainsbury, S. M., Russell, A., & Hing, N. (2014). An investigation of social casino gaming among land-based and Internet gamblers: A comparison of socio-demographic characteristics, gambling and co-morbidities. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 126–135. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.031

Gainsbury, S. M., Russell, A. M., King, D. L., Delfabbro, P., & Hing, N. (2016). Migration from social casino games to gambling: motivations and characteristics of gamers who gamble. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 59-67.

Gainsbury, S. M., King, D. L., Abarbanel, B., Delfabbro, P. & Hing, N. (2015). Convergence of gambling and gaming in digital media. Centre for Gambling Education & Research, Southern Cross University.

Gradwell, H. (2013). How to stop your kids accidentally spending your money on apps and games. Think Money, April 12. Located at: http://www.thinkmoney.co.uk/news-advice/stop-kids-accidentally-spending-your-money-on-apps-and-games-0-4111-0.htm

Griffiths, M. D. (2015) Adolescent gambling and gambling-type games on social networking sites: Issues, concerns, and recommendations. Aloma, 33(2), 31-37.

Griffiths, M. D., King, D. L., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2014). The technological convergence of gambling and gaming practices. In D. C. S. Richard, A. Blaszczynski & L. Nower (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of disordered gambling (pp. 327–346). West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Griffiths, M., & Wood, R. (2007). Adolescent Internet gambling: Preliminary results of a national survey. Education and Health, 25, 23–27.

Gupta, R., & Derevensky, J. (2011). Understanding the etiology of youth problem gambling. In J. Derevensky, D. Shek, & J. Merrick (Eds.), Youth gambling problems: The hidden addiction. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Hayer, T., Griffiths, M.D.,&Meyer, G. (2005). The prevention and treatment of problem gambling in adolescence. In T.P. Gullotta & G. Adams (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent behavioral problems: Evidence-based approaches to prevention and treatment (pp. 467–486). New York: Springer.

Hollingshead, S., Kim, H. S., Wohl, M. J. A., & Derevensky, J. (2016). The social casino gaming-gambling link: Motivation for playing social casino games determine whether gambling increases or decreases. Journal of Gambling Issues, 33, 52-67.

Ipsos MORI (2006). Under 16 s and the National Lottery: Final report. London: National Lottery Commission.

Jackson, A. C., Dowling, N., Thomas, S. A., Bond, L., & Patton, G. (2008). Adolescent gambling behaviour and attitudes: A prevalence study and correlates in an Australian population. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 6(3), 325–352.

Jacques, C., Fortin-Guichard, D., Bergeron, P. Y., Boudreault, C., Lévesque, D., & Giroux, I. (2016). Gambling content in Facebook games: A common phenomenon?. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 48-53.

Juniper Research (2016). White paper: The rise of virtual reality. Available from: http://www.juniperresearch.com/document-library/white-papers/the-rise-ofvirtual-reality

Kharpal, A. (2016). Virtual reality gambling expected to grow 800 percent by 2021driven by ‘high rollers’. CNBC News, October 16. http://www.cnbc.com/2016/10/10/virtual-reality-gambling-expected-to-grow-800-percent-by-2021-driven-by-high-rollers.html

Kim, H. S., Wohl, M. J. A., Salmon, M., Gupta, R., & Derevensky, J. (2014). Do social casino gamers migrate to online gambling? An assessment of migration rate and potential predictors. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(4), 1819–1831. doi:10.1007/s10899014-9511-0

Kim, H. S., Salmon, M., Wohl, M. J., & Young, M. (2016a). A dangerous cocktail: Alcohol consumption increases suicidal ideations among problem gamblers in the general population. Addictive Behaviors, 55, 50–55.

Kim, H. S., Wohl, M. J., Gupta, R., & Derevensky, J. (2016). From the mouths of social media users: A focus group study exploring the social casino gaming–online gambling link. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(1), 115-121.

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P.H., Doh, Y. Y., Wu, A. M. S, Kuss, D. J., Pallesen, S., Mentzoni, R., Carragher, N. & Sakuma, H. (2017). Policy and Prevention Approaches for Disordered and Hazardous Gaming and Internet Use: an International Perspective. Society for Prevention Research.

King, D. L., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2016). Early exposure to digital simulated gambling: A review and conceptual model. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 198–206.

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Deverensky, J. & Griffiths, M. (2012). A review of Australian classification practices for commercial video games featuring simulated gambling. International Gambling Studies. http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rigs20

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., & Griffiths, M. (2010). The convergence of gambling and digital media: Implications for gambling in young people. Journal of Gambling Studies, 26, 175–187. doi:10.1007/s10899-009-9153-9

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Kaptsis, D., & Zwaans, T. (2014). Adolescent simulated gambling via digital and social media: An emerging problem. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 305–313. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.048

King, D.L., Gainsbury S.M., Delfabbro, P. H., Hing, N., & Abarbanel, B. (2015). Distinguishing between gaming and gambling activities in addiction research. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 4(4), pp. 215–220.

King, D.L., Russell, A., Gainsbury, S., Delfabbro, P. H. & Hing, N. (2016). The cost of virtual wins: An examination of gambling-related risks in youth who spend money on social casino games. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 5(3), pp. 401–409

Korn, D., Hudson, T. & Reynolds, J. (2005). Commercial gambling advertising: Possible impact on youth knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behavioural intentions. Guelph, ON: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

Korn, D., Shaffer, H., Gambling (1999) and the health of the public: Adopting a public health perspective. Journal of Gambling Studies, 15, 289–365.

Csgo Coinflip

Langer, E. J. (1975). The illusion of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32(2), 311–328.

Martin, C. (2014, Summer). Big data and social casino gaming. Canadian Gaming Lawyer Magazine. Retrieved from https://imgl.org/sites/default/files/media/bigdataandsocialcasinogaming_christinemartinjd_cgl_summer2014.pdf

Matheson, K., Wohl, M. J., & Anisman, H. (2009). The interplay of appraisals, specific coping styles, and depressive symptoms among young male and female gamblers. Social Psychology, 40, 212–221.

McBride, J., & Derevensky, J. (2009). Internet gambling behaviour in a sample of online gamblers. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7, 149–167.

McBride, J., Derevensky, J., & Gupta, R. (2006). Internet gambling among youth: A preliminary examination. Paper presented at the Responsible Gambling Council (Ontario) annual conference (Toronto, Ontario, Apri).

Messerlian, C. & Derevensky, J. (2006). Social marketing campaigns for youth gambling prevention: Lessons learned from youth. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 4(4), 294–306.

Messerlian, C., Derevensky, J., & Gupta, R. (2005). Youth gambling problems: A public health perspective. Health Promotion International, 20, 69–79.

Monaghan, S. M., & Derevensky, J. (2008). An appraisal of the impact of the depiction of gambling in society on youth. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 6(4), 537-550.

Morgan Stanley (2012). Social gambling: Click here to play. Morgan Stanley Research: Global.

Moore, S. M., & Ohtsuka, K. (1999). The prediction of gambling behaviour and problem gambling from attitudes and perceived norms. Social Behaviour and Personality, 27(5), 455–466.

Olason, D., Kristjansdottir, E., Einarsdottir, H., Bjarnarson, G., & Derevensky, J. (2011). Internet gambling and problem gambling among 13 to 18 year old adolescents in Iceland. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 9, 257–263.

Owens, M. D. J. (2010). If you can’t tweet’em, join’em: The new media, hybrid games, and gambling law. Gaming Law Review and Economics, 14(9), 669–672. doi:10.1089/glre.2010.14906

Parke, J., Wardle, H., Rigbye, J., & Parke, A. (2012). Exploring social gambling: Scoping, classification and evidence review. Birmingham: Gambling Commission.

Petry, N., & Weinstock, J. (2007). Internet gambling is common in college students and associated with poor mental health. The American Journal on Addictions, 16, 325–330.

Petry, N. M., Stinson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. (2005). Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 564–574.

PRNewswire. (2012, January 12). International game technology to acquire social gaming company double down interactive. International Game Technology. Retrieved from http://www.igt.com/company-information/news-room/news-releases.aspx?NewsID=1647893.

Sapsted T. Social casino gaming: Opportunities for 2013 and beyond. London: FC Business Intelligence; 2013.

Saugeres, L., Thomas, A., & Moore, S. (2014). “It wasn’t a very encouraging environment”: Influence of early family experiences on problem and at-risk gamblers in Victoria, Australia. International Gambling Studies, 14(1), 132–145. doi:10.1080/144597 95.2013.879729

Schrans, T., Schellinck, T., & Walsh, G. (2001). 2000 regular VL players follow up: A comparative analysis of problem development and resolution. Nova Scotia: Nova Scotia Department of Health, Addiction Services.

Shead, N. W., Derevensky, J., & Gupta, R. (2010). Risk and protective factors associated with youth problem gambling. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 22(1), 39–58.

SuperData (2012). The house doesn’t always win. Evaluating the $1.6b social casino games market. Superdata blog. Retrieved from http://www.superdataresearch.com/blog/evaluating-the-social-casino-games-market/

Superdata. (2015). Global games market. New York: Superdata.

Talbot, B. (2013). My 6yr-old spent £3,200 playing iPhone game’ – How to stop it. Money Saving Expert. February 19. Located at: http://www.moneysavingexpert.com/news/phones/2013/02/kids-spent-3200-iphone-avoid-app-charge-hell

Teichert, T., Gainsbury, S. & Mühlbach, C. (2017) Positioning of online gambling and gaming products from a consumer perspective: A blurring of perceived boundaries, Computers in Human Behavior, doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.025

Thomas, A. C., Allen, F. C., & Phillips, J. (2009). Electronic gaming machine gambling: Measuring motivation. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(3), 343–355. doi:10.1007/s10899-009-9133-0

UK Gambling Commission (2017). Virtual currencies, eSports and social casino gaming – position paper.

Volberg, R., Gupta, R., Griffiths, M., Olason, D., & Delfabbro, P. (2010). An international perspective on youth gambling prevalence studies. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 22, 3–38.

Wohl, M. J. A., & Enzle, M. E. (2002). The deployment of personal luck: Sympathetic magic and illusory control in games of pure chance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1388–1397.

Wohl, M. J. A., Salmon, M. M., Hollingshead, S. J. & Kim, H. S. (2017). An examination of the relationship between social casino gaming and gambling: The bad, the ugly, and the good. Journal of Gambling Issues, Issue 35

Wohl, M. J. A., Stewart, M. J., & Young, M. M. (2011). Personal luck usage scale (PLUS): Psychometric validation of a measure of gambling-related belief in luck as a personal possession. International Gambling Studies, 11, 7–21.

ARTICLES

Get our monthly newsletter

Interested in how gaming intersects with health, wellbeing and safety? Sign up to our newsletter. Every month we send a collection of news stories and articles. No sales, no spam...

We believe skin gambling sites are not currently safe for players due to the threat that players will lose the skins that they deposit due either to a site shutting down and not refunding deposits or Valve freezing the Steam account of the site and confiscating all skins.

This is true both for “jackpot” sites and for CSGO skin betting sites like CSGO Lounge. So where can players bet on CS:GO and other esports?

What are the best alternatives to CSGO Skin gambling sites?

Real money CSGO gambling sites have always been better

The initial appeal of skin betting was driven by a few factors:

- Ease of use: Signing up for sites was typically a breezy process. Beyond access to their Steam URL, players were never asked to fork over sensitive personal information, like their SSN.

- Flexibility: Skin betting sites varied widely, offering everything from match betting to casino-style gambling. It’s this broad appeal that contributed to the market’s success.

- Worldwide Market: Players from the U.S. and other jurisdictions where sports betting is not regulated could freely participate.

- No real-money deposits: By betting skins, users bypassed the sometimes arduous process of making a real-money deposit on a gambling site.

Yet, with all these benefits came one major caveat: skin betting was operating in a completely unregulated environment, thereby subjecting users to a bevy of vulnerabilities.

On the flip side, esports cash betting sites operate in a secure, regulated environment where:

Skins Gambling Companies

- Safeguards are set up to ensure personal and financial protection.

- Users must be able to verify their age before placing wagers. By contrast, some CS:GO skins gambling sites did not require age verification, opening the door for minors to place wagers.

- A site’s ability to operate is not dependent on a third-party like Valve — which has the ability to freeze operator accounts at its discretion.

- Operators have established a measure of trust via reliable payouts, 24/7 access to funds and customer support, and a dearth of server outages and unexpected site shutdowns.

- Employees, or anyone connected to the operator, cannot place wagers on or have advance knowledge of the outcome of an event.

The last point is bound to resonate with CSGO skin gambling users, as there have been myriad accounts of vested parties knowing the outcome of events before they happen.

One notable example that recently came to light is that of a Twitch stream partner of CSGODiamonds.com, who was given knowledge of game results ahead of time.

Other similar scandals of employees toying with odds have also come to the surface of late, at an alarming frequency.

Inside Valve’s crackdown on CS:GO gambling sites

On July 19, Valve sent a cease and desist letter to 23 skin wagering sites that used Steam to conduct activities it said violated the API’s terms of service.

Why did Valve crackdown on CSGO skin betting?

As was the case with daily fantasy sports, when skin betting was a relatively small and seemingly innocuous industry, it flew under the radar. Countless gamblers could easily get started for free with a CS GO casino code, and many – including underage gamblers – were hooked.

But when the industry came to prominence, which it did in a big way (an article by Bloomberg states that the number of users grew 1,500 percent over the course of two years), Valve was presumably forced to take notice.

While Lounge was the first site mentioned in the letter, Valve’s action was likely spurred on by a series of scandals involving four different skin gambling sites during the summer of 2016. Two of those sites’ owners were found to have wagered and won on their own sites using house money, without disclosing their ownership position. A third paid a sponsored player more than $100,000 to promote the site while it admittedly rigged the outcomes of his rolls to severely increase his chances of winning. A fourth site’s owners were directly linked to a professional CS:GO franchise, which Valve ostensibly prohibits.

By Aug. 1, Valve had not only named all four sites in C&D actions, but all the sites had shut down, as well.

A class-action lawsuit filed by a CS:GO player in June, signifying that Valve facilitated the growth of an illicit online gambling industry, was probably the proverbial icing on the cake.

Valve’s CSGO casino crackdown growing more intense

With Valve’s position on skin betting growing increasingly intolerant, affected operators find themselves searching for an alternative means of sustaining their esports betting operations.

Below is a brief timeline of the major events surrounding Valve’s crackdown:

- MAY 2016: Skin gambling site CSGOStakes closes with no notice, failing to reimburse players who had skins or site credit still on deposit.

- JUNE 2016: A popular CS:GO streamer paid to promote a skin gambling site reveals that he was told in advance by site owners when he would win or lose. This was done to make his streaming of gambling on the site “more entertaining.”

- JUNE 2016: A lawsuit seeking class-action status is filed against CS:GO developer Valve. The suit claims that Valve is complicit in the operation and growth of the skin gambling economy.

- JUNE 2016: A major skin gambling site pulls out of the U.S. market in an apparent response to legal or regulatory concerns.

- JULY 2016: Two popular esports personalities who aggressively promoted a skin gambling site are revealed to be owners of said site, a fact that was not obviously disclosed in their promotion of the site.

- JULY 2016: Valve requests that skin gambling sites stop utilizing some aspects of the Steam platform.

- JULY 2016: A popular roulette-style skin gambling site closes in reaction to Valve’s announcement, but announces a plan and timeline for allowing players to withdraw their balances prior to full shutdown.

- JULY 2016: Twitch announces a ban on streams containing skin gambling on the basis that such streams violate Valve’s TOS.

- JULY 2016: Esports journalist Richard Lewis raises allegations that another major esports personality maintained an undisclosed ownership stake in a skin betting site while promoting said site.

- JULY 2016: Valve issues cease-and-desist notices to 23 skin gambling sites. A handful comply, but most continue to operate.

Predicting the future of legit CSGO skin gambling sites

Where CSGO skin gambling goes from here largely depends on how aggressive a stance Valve takes in curtailing the activity. As of now, I’d describe its current position as moderate.

Following Valve’s announcement, several high profile CS:GO skin betting sites ceased operations. However, there are strong indicators that the shutdowns are only temporary until a suitable loophole can be found.

The language of a few “goodbye” announcements even suggests that operators were anticipating this move by Valve, and have been preparing for it for months.

In truth, Valve cannot completely eliminate skin betting unless it first disallows users from trading items — a radical step that it has shown no indication of wanting to take.

Until then, skin betting will persist in some capacity, with Valve continually having to play a cat-and-mouse game as the industry struggles to remain one step ahead. Some, like most popular skin betting site CSGOLounge, are conducting business as usual and may stick with the current model until it is no longer viable to do so.

That being said, as more and more skin betting sites fall by the wayside in the coming weeks and months, expect the divide between skin betting sites and regulated esports gambling sites to shrink.

As for the long term, it’s presumable that skin betting will become regulated in select jurisdictions, particularly in Europe. However, the (overly) restrictive nature of sports betting laws in the U.S. will make the path toward regulation stateside a difficult one, at best.

A brief history of CS:GO skin gambling sites

The introduction of weapon skins sparked a growing interest in the CS:GOgambling scene.

Valve, the creator of Counter-Strike, launched an open market for community members to create items with developer tools. Community votes determine which items are introduced to the game.

Players receive items and cases through random drops, and cases can be opened for $2.50 to generate skins within the game. Market sales determine item values by supply-demand interactions, giving each item a value based on its rarity, aesthetic desirability, and wear.

Essentially, CS:GO facilitates currency-exempt gambling by using virtual capital. The majority of people who gamble often play Counter-Strike, but also actively follow streams on Twitch.

Streamers have, in the past, grown the popularity of sites solely by gambling while on-air. So, the demand for valuable items grew Counter-Strike item betting beyond the scope of competitive games.

Let’s take a look at how, why, and when these services evolved.

CS:GO Lounge – the original CS GO casino

CS:GO Lounge was the first betting service to take the community by storm. It seems like the project started in 2011 (that’s the date of its Facebook group’s first post), but only gained significant momentum by 2013.

Professional games are registered on the site for players to gamble, and the odds are determined by the total amount of bets on each team.

Sites like these can be profitable if you closely follow games and community news. By betting against the odds and understanding them better than the average user, you can reduce the need for luck.

CSGL is simple and straight to the point. Looking back, this was a key stepping stone for the modern esports gambling culture.

CS:GO jackpot games

Jackpot games were first popularized by Skin Arena in April 2015. It did so by tapping into a slightly different market than CSGL.

The chance to win expensive skins with small amounts of money intrigued all types of casual skin owners. Jackpot games follow a very simple principle. They allow players to add skins to a pot (with a new pot every minute or two).

A player’s chance of winning is proportional to the amount of skins that bettor deposited (if your skins compose 5 percent of the pot, you have a 5 percent chance of winning).

Naturally, people with big inventories dominated these sites because consistent betting had the highest trade-off. Also, wealthy players often claimed entire pots by throwing $1000+ in the last seconds, essentially ‘sniping’ other people’s items.

These sites lost popularity in the later months of 2015 because the same people kept winning. Also, most of these sites asked $5 for a minimum bet, which is too much for people who simply deposit skins that were collected by playing.

The community wanted a game that could let anyone win.

CS:GO blackjack

CS:GO Blackjack was one of the firstCS:GO casino games to use skin items as its gambling medium. Although in part, the time of its release (around April 2015) caused it to be overshadowed by jackpot games like Skin Arena, it still made multiple appearances on streams and sponsored several relevant players.

Blackjack also had the issue of not accepting low-value skins. Its two dollars per skin cut-off excluded a notable portion of the gambling market. Following developments in the market, proved that there was money to be made in those untapped corners of the industry.

CS:GO coin flip sites

Skins Gambling Com Online

Coin flip games, first made famous by CSGOWild in October 2015 (and followed by other CS GO 1v1 sites), were the simplest form of CS:GO gambling to emerge.

CSGOWild was also the first service from the websites on this list to accept low-value skins. This, in combination with a simple referral system, really made the website take off.

Brief and simple games help stream entertainment, particularly when a lot of money is on the line. So, CSGOWild took the market by storm, even though the timing of its release caused it to share the spotlight with CSGODouble.

CS:GO roulette

With blackjack and jackpot games paving the way for more involved forms of betting, roulette games soon flooded the market at the end of 2015.

CSGODouble was the first successful roulette implementation. Famous players quickly noticed that people enjoyed watching their reactions while playing, giving them personal incentive to bet while streaming.

Even though each roulette result is created independently from a random number generator, forums were soon infested with different betting strategies and people who claimed to know the golden pattern. It seems that gamers, even when gambling, like to approach the process much the same way they play competitive video games.

CS:GO dice games

Dice games gained popularity around March 2016. They claimed a large portion of the market by offering several different ways of placing bets. Odds, number of bets, winning criteria can all be adjusted under the limits inherent to the game.

So, customization options are in part why flexible CSGO sites like CSGODiamonds became successful. At the same time, streamers introduced the game at a time when roulette and coin flip games started feeling stale. So, a large portion of the market was left open.

Metagame speculation for dice games paved the way for something more engaging and complicated and as such still stand as the newest successful betting service.

There have been six different popular CS:GO skin betting website types to date. Although these changes might seem random at first, they are the consequence of market openings that are discovered by keen entrepreneurs.

Nobody knows how this market will develop. Virtual item gambling debates float to the surface every so often, making the future uncertain.

As for the progression of the games themselves? My opinion is that we can expect to see more sophisticated games as time goes on. Creativity is the only limiting factor.

How CS:GO skin betting works

Skins are virtual items that can be used in games like Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO). The term “skin” is derived from the typical function of these virtual items: changing the appearance of a player’s in-game avatar, weapons, or equipment.

There are a number of ways for players to acquire skins. In CS:GO, players can acquire skins by:

- Receiving them during gameplay.

- Receiving them as a promotional giveaway (often around major CS:GO events).

- Trading with other players.

- Purchasing skins on a variety of marketplaces.

How do people bet skins?

Forget for a moment the practical application of a skin (changing the appearance of a character in a video game) and instead think of a skin as a simple unit containing value – not unlike a casino chip.

Skins Gambling Com Site

Like a casino chip, a CS:GO skin can be traded between the player and the house. That basic functionality allows skins to serve as a de facto currency that can power basically any type of gambling product you can imagine. Here’s how it works:

- Players “deposit” a skin at a skin betting site (popular types of sites include sportsbooks, lotteries, roulette, and coin flips) by transferring the skin to the skin betting site.

- They gamble using their deposited skins (or in some sort of internal currency that the player receives in exchange for their skin).

- If they win, they’re paid in additional skins, which they “cash-out” by requesting that the skin betting site transfer skins back to the player.

Once players have skins in their Steam account, they can:

- Leave the skins dormant in their inventory.

- Use the skins to change the appearance of their weapons.

- Trade skins with other players.

- Sell skins on the Steam marketplace for Steam credit (not cash) that can be used to buy other skins and games via Steam.

- Exchange skins for cash on third-party sites outside of Steam.

Here’s a visual explanation of the process:

Note that not all video games with skins or other virtual items allow those items to be transferred between players. Among popular esports, CS:GO and Dota 2 are unique in allowing the easy movement of virtual items between accounts.